Group Decision-Making: Three Areas to Check for Less Friction

A lot of my attention recently has gone into trying to better understand what causes frustration and loss of engagement in group decision-making and group exploration.

While there are many dynamics at play, there are three that have become clearer to me.

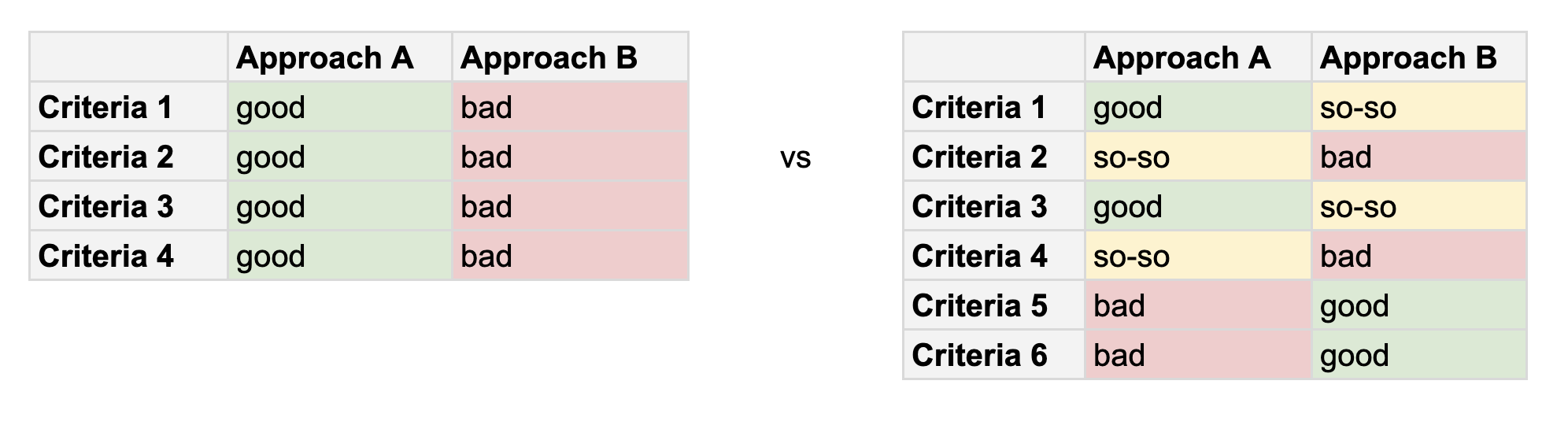

First, criteria. Criteria for decision-making might not be clear, or there might be no intention to clarify the criteria. If that's the case, people tasked with exploration may invest effort, enthusiasm, and energy in things that don't actually add value to the decision. That can be deeply frustrating: people want to contribute, yet see their work effectively go to waste.

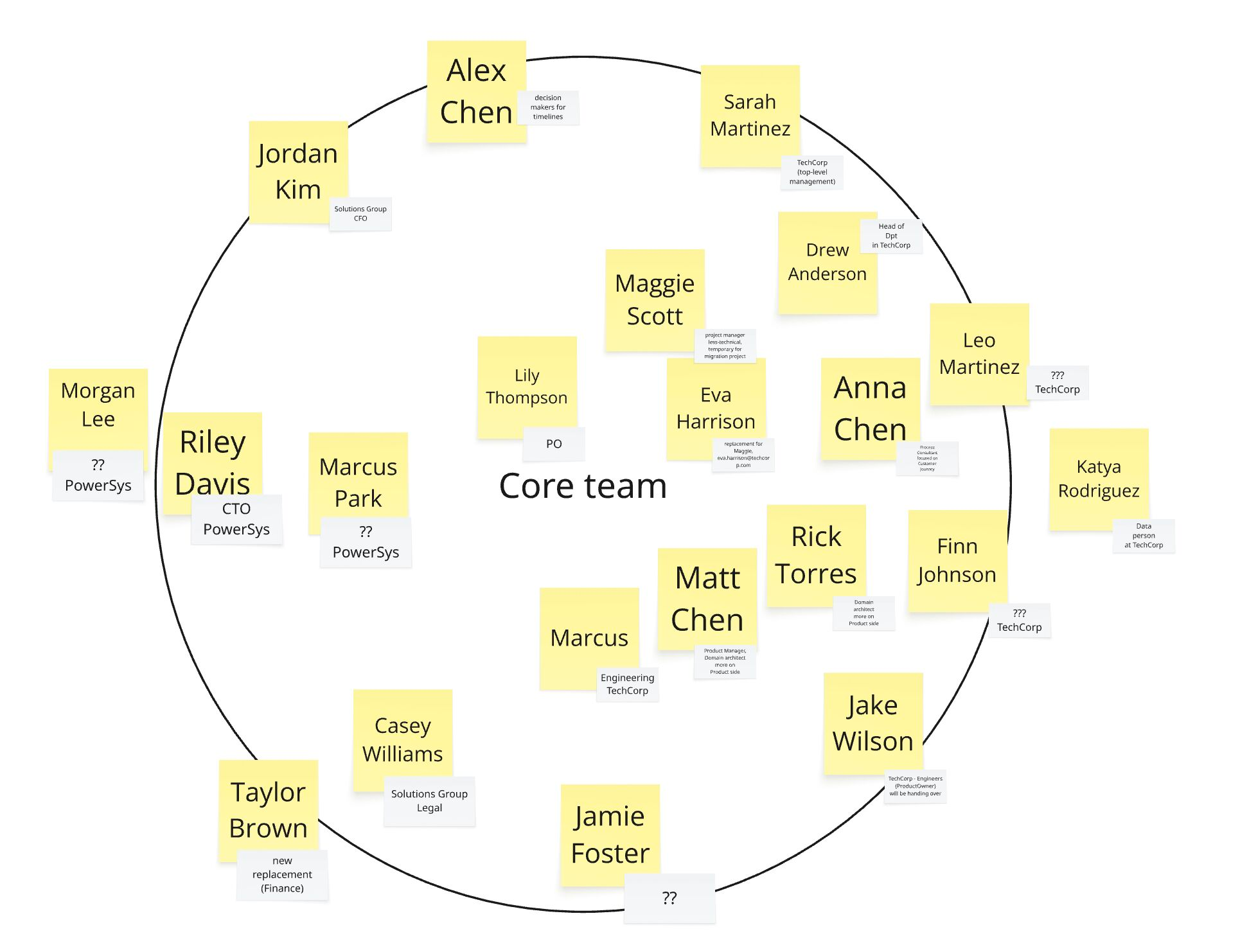

Second, authority and hierarchy. There could be someone in the group who has a higher position and is, in reality, the decision-maker. If this person has already made a decision on part of the problem, but communicates the whole process as collaborative and democratic, it can create confusion. People might assume the process is egalitarian and that they can democratically steer the outcome, when in fact they cannot. It seems healthier to acknowledge these roles explicitly, so the group can support the decision-maker by filling in gaps where they actually matter.

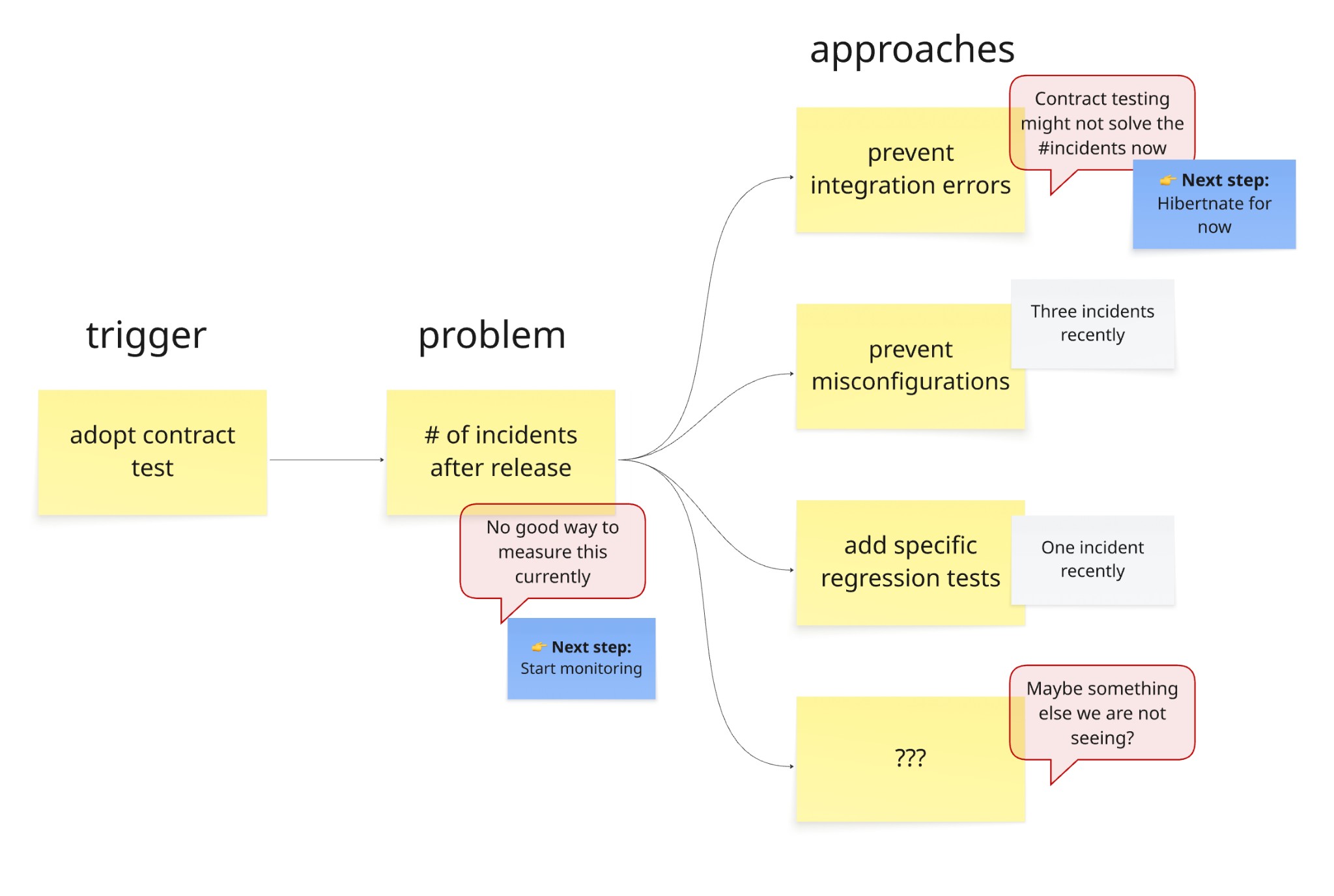

Third, consolidation. Many people seem to appreciate consolidation, that is, higher-level summaries of what a group has learned so far. I think this is because people value big-picture clarity. With the big picture, people can better orient themselves in the problem space, see the next steps and also see how their effort contributes to the overall effort.

Some questions one can ask:

- Criteria: Are people aligned on the decision criteria? Do people interpret the criteria, and their weights, in the same way?

- Decision ownership: Is there an implicit owner of the decision? How is that role recognized within the group? How are decisions and remaining open points communicated back to everyone?

- Consolidation: Is learning being consolidated and summarized at a high level?

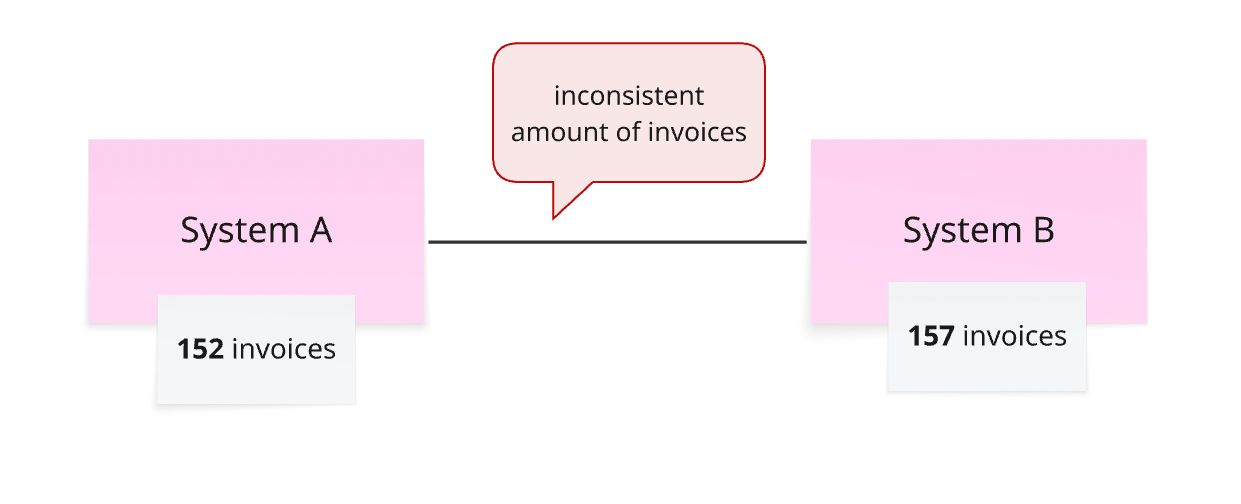

Some inconsistencies are ok, some are not. Without clarity on the required degree of consistency, you might find yourself in confusing situations.

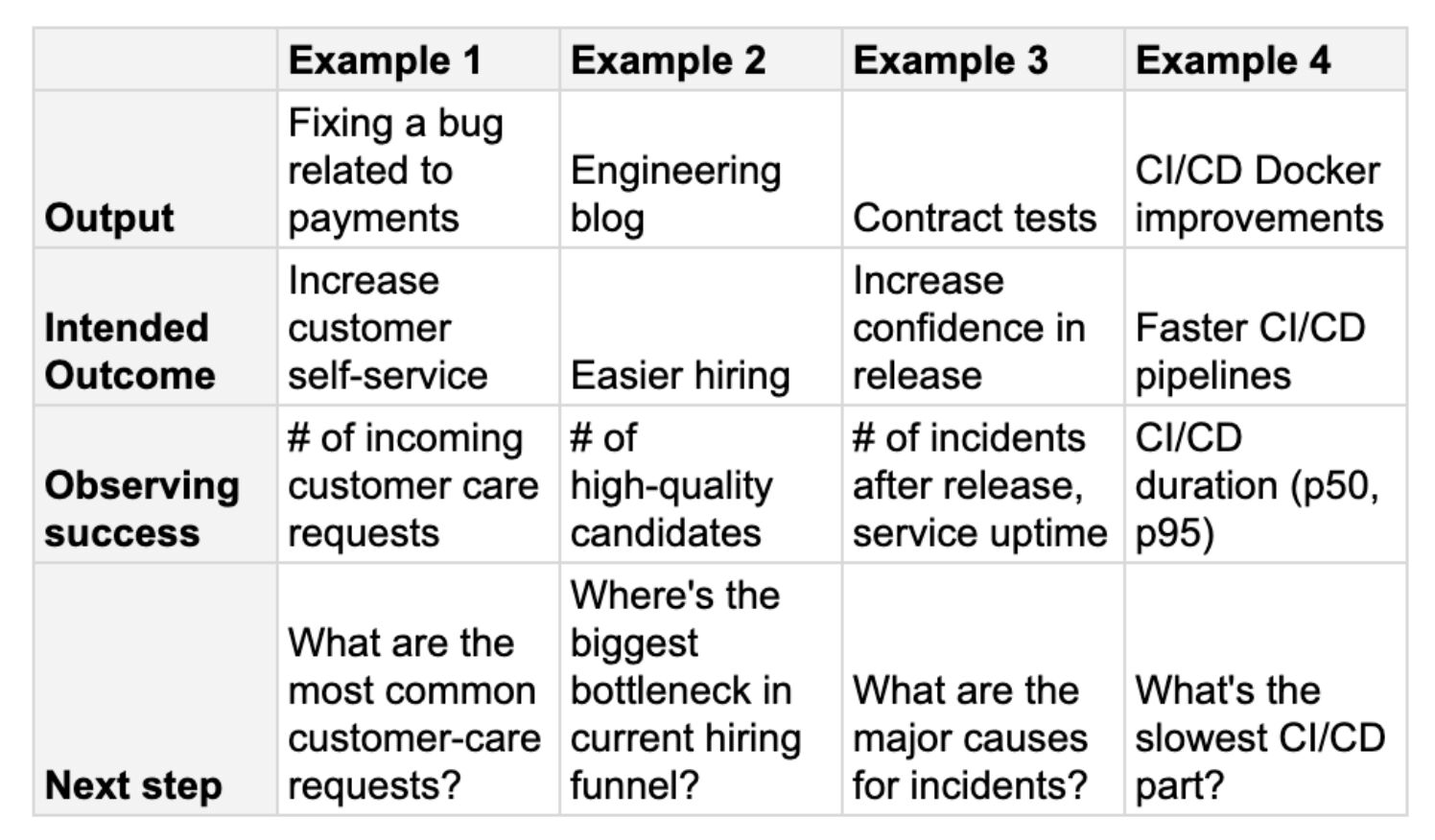

Some inconsistencies are ok, some are not. Without clarity on the required degree of consistency, you might find yourself in confusing situations. In engineering, things often seem impossible to measure. Especially the soft, intangible things. But if something is valuable, it should be observable in some way.

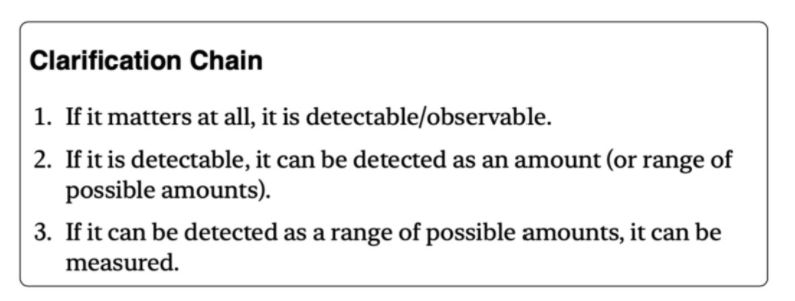

In engineering, things often seem impossible to measure. Especially the soft, intangible things. But if something is valuable, it should be observable in some way.